1. Introduction

Groups, semigroups and categories are ubiquitous in Mathematics. The dynamical systems associated with such structures are usually assumed to satisfy some form of associativity, roughly stating that “performing certain related operations in any order will always yield the same result”. This is clearly the case, for example, when considering group actions. Moreover, different components of a given system play different roles: Given a left action of a group $G$ on a set $X$, the elements of $G$ can be composed both with elements of $G$ (on either side) and with elements of $X$ on their right (via the action), however elements of $X$ can only be composed with elements of $G$ on their left. This leads us to consider partially defined operations.

Semigroupoids are an algebraic abstraction of these concepts: they are sets with partially defined binary operations with are associative in a precise way. In particular, the two most prominent examples of semigroupoids are categories and semigroups.

Whereas the most common categories one first encounters consist of unrelated objects of a given signature, such as the categories of rings, topological spaces, posets, etc… and certain structure-preserving maps between them, we consider a more algebraic-geometric approach: categories (and semigroupoids) ought to be regarded as collections of transformations between subobjects of a single object. The classical version of this approach is well-established, where one seeks to understand a given object by looking at its automorphism group. This is the first motivation for this work.

This approach ‒ to study an object by analyzing its “partial automorphisms” ‒ has been popularized in the contexts of Topological Dynamics and Operator Algebras mainly after the introduction of partial actions of groups by Exel on his study of the structure of $C^*$-algebras endowed with circle actions in [MR1276163]. This turned out to be a rich an fruitful research direction, since it allows one to consider algebras and topological dynamical systems which are not induced (in any natural fashion) by a group action, but rather from transformations among its subsets (see [arxiv1804.00396], MR3789176], MR2645883], for example).

A variation on the “partial transformation” approach was taken by Sieben in [MR1671944], MR1456588], who instead considered actions of inverse semigroups on topological spaces and algebras. Inverse semigroups have been thoroughly studied in the last century, which provides solid foundation for this approach.

Another approach to Topological Dynamics and Operator Algebras, and which in fact predates the works above, is the usage of groupoids, which have played a central role in the theory of $C^*$-algebras since Renault's seminal work [MR584266], since they provide a geometric counterpart to a large class of (non-commutative) $C^*$-algebras. In simple terms, and as an interpretation of [MR2460017], groupoids are the “non-commutative spectra” of “non-commutative, dynamical $C^*$-algebras”.

Groupoids, partial actions of groups, and actions of inverse semigroups ‒ or more generally partial actions of inverse semigroups ‒ are related via the constructions of “groupoids of germs” and “crossed products”. We refer to [MR2045419], arxiv1804.00396], MR3743184], MR3851326], MR2799098], MR1724106], MR1671944], MR2565546]. In fact, groupoids and inverse semigroups may be seen as dual to each other, via the non-commutative Stone duality of Lawson-Lenz, [MR3077869]. We also refer to [MR2969047], MR2644910], MR2304314] for related studies.

Actions of groupoids have also appeared throughout the literature, in the context of Lie theory ([MR2012261]), algebraic topology ([MR2273730]), operator algebras and topological dynamics ([MR2982887], MR2969047], MR2941279]). A generalization of groupoids and inverse monoids, called inverse categories, were initially introduced in [MR0506554] and have been considered in recent work, e.g. in the study of tilings ([MR1736698]), logic and recursion theory ([MR1871071], MR3605681]) and crossed product algebras ([MR2959793]).

The main goal of this article is to study the structure of inverse semigroupoids, which are a common generalization of both inverse semigroups and groupoids. First we begin by comparing the notions of semigroupoid used in [MR3597709], MR915990] to that of [MR2754831], which is more general. After that, we introduce inverse semigroupoids and prove some basic facts about their structure (some which had already been proven in [MR3597709]). We follow with a representation theorem, which is an analogue of Cayley's Theorem for groups and the Vagner-Preston theorem for inverse semigroups. It motivates a notion of actions ‒ and more generally $\land$-preactions and partial actions ‒ of inverse semigroupoids on semigroupoids, in a manner which covers previously used notions for inverse semigroups and for groupoids. These are used to construct “semidirect products” which generalize transformation groupoids of partial group actions, semidirect products of inverse semigroups, semidirect products of groupoids, among others.

In the third section we look at topological semigroupoids, specializing to the étale inverse semigroupoid case, and generalize some results known for topological groupoids to this setting. The fourth section generalizes some constructions from the theory of inverse semigroups, and we describe their categorical properties explicitly. The fifth and last section contains a generalization of non-commutative Stone duality to the context of inverse semigroupoids.

Notation and running conventions

The domain and codomain of a map $f$ are denoted by $\dom(f)$ and $\cod(f)$, respectively. The image of a subset $A\subseteq\dom(f)$ is denoted as $f(A)$, and the range of $f$ is $\ran(f)\defeq f(\dom(f))$. Note that $\cod(f)=\ran(f)$ if and only if $f$ is surjective.

Given maps $f_i\colon X_i\to Y_i$ ($i=1,2$), we define $f_1\times f_2\colon X_1\times X_2\to Y_2\times Y_2$ as $(f_1\times f_2)(x_1,x_2)=(f_1(x_1),f_2(x_2))$. If $X_1=X_2\eqdef X$, we define $(f_1,f_2)\colon X\to Y_1\times Y_2$ as $(f_1,f_2)(x)=(f_1(x),f_2(x))$. The identity map of a set $X$ is denoted as $\id_X$, and more generally $\id_{\mathcal{C}}$ stands for the identity functor of a category $\mathcal{C}$.

We denote as $\mathbb{N}=\left\{0,1,2,\ldots,\right\}$ the set of non-negative integers, and as $\mathbb{N}_{\geq 1}=\mathbb{N}\setminus\left\{0\right\}$ the set of positive integers.

We assume familiarity with inverse semigroups and étale groupoids. The main references are [MR1694900], MR1724106] (see also the author's PhD thesis [cordeirothesis]). A semilattice is a poset $(P,\leq)$ admiting binary meets (infima), and is always regarded as an inverse semigroup under meets: $ab=a\land b=\inf\left\{a,b\right\}$ for all $a,b\in P$.

1.1. Setoids, bundles and partitions

A setoid is a pair $(X,R)$, where $X$ is a set and $R$ is an equivalence relation on $X$. Equivalently, a setoid is a principal groupoid. A morphism of setoids $(X,R_X)$ and $(Y,R_Y)$ is simply a relational morphism, that is, a map $f\colon X\to Y$ such that $(f\times f)(R_X)\subseteq R_Y$. Equivalently, a morphism of setoids, seen as principal groupoids, is simply a groupoid homomorphism.

A bundle or fibration is a function $\pi\colon X^{(1)}\to X^{(0)}$. $X^{(0)}$ is called the base space, and we say that $X^{(1)}$ is fibred over $X^{(0)}$, or that $\pi$ is a bundle over $X^{(0)}$. Although of most insterest are the surjective bundles, we do not make such an assumption.

A morphism between bundles $(X^{(0)},X^{(1)},\pi_X)$ and $(Y^{(0)},Y^{(1)},\pi_Y)$ is a pair $f=(f^{(0)},f^{(1)})$ of maps $f^{(i)}\colon X^{(i)}\to Y^{(i)}$ ($i=0,1$) such that $f^{(0)}\circ\pi_X=\pi_Y\circ f^{(1)}$. In other words, bundles and their morphisms are simply the category of arrows of $\cat{Set}$, the category of sets and functions (see [MR1712872]).

A partition is a pair $(X,\mathscr{P})$, where $X$ is a set and $\mathscr{P}$ is a partition of $X$ (i.e., a collection of nonempty, pairwise disjoint subsets of $X$ such that $\bigcup\mathscr{P}=X$). A morphism between partitions $(X,\mathscr{P}_X)$ and $(Y,\mathscr{P}_Y)$ is a map $f\colon X\to Y$ such that for every $A\in\mathscr{P}_X$, there exists $B\in\mathscr{P}(Y)$ such that $f(A)\subseteq B$.

Setoids, surjective bundles and partitions are equivalent concepts. More precisely, the categories $\cat{Std}$, $\cat{Bdl}_{\mathrm{sur}}$ and $\cat{Part}$ which they respectively define are equivalent:

-

Given a setoid $(X,R)$, we construct the bundle $(X/R,X,\pi_X)$, where $X/R$ is the quotient space and $\pi_X\colon X\to X/R$ is the quotient map. Given a morphism of setoids $f\colon (X,R_X)\to (Y,R_Y)$, there exists a unique map $f^{(0)}\colon X/R_X\to Y/R_Y$ such that $f^{(0)}\circ\pi_X=\pi_Y\circ f$. Then $(f^{(0)},f)$ is a morphism of bundles.

-

Given a bundle $(X^{(0)},X^{(1)},\pi)$, we consider the partition $\mathscr{P}_X=\left\{\pi^{-1}(x):x\in\pi(X^{(1)})\right\}$ of $X^{(1)}$. Given a bundle morphism $f=(f^{(0)},f^{(1)})\colon(X^{(0)},X^{(1)},\pi_X)\to (Y^{(0)},Y^{(1)},\pi_Y)$, the map $f^{(1)}$ is a morphism of partitions $f^{(1)}\colon (X^{(1)},\mathscr{P}_{X})\to (Y^{(1)},\mathscr{P}_{Y})$.

-

Any partition $(X,\mathscr{P})$ induces an equivalence relation $R_{\mathscr{P}}$ on $X$ as

\begin{equation*} R_{\mathscr{P}}=\left\{(x,y)\in X\times X:\text{there exists }A\in\mathscr{P}\text{ such that }x,y\in A\right\} \end{equation*}Given a morphism of partitions $f\colon (X,\mathscr{P}_X)\to (Y,\mathscr{P}_Y)$, the same map $f\colon X\to Y$ is also a morphism of setoids.

All of these constructions are functorial. If we denote $F\colon \cat{Std}\to\cat{Bdl}_{\mathrm{sur}}$, $G\colon \cat{Bdl}_{\mathrm{sur}}\to\cat{Part}$ and $H\colon\cat{Part}\to\cat{Std}$ the functors described above, then $H\circ G\circ F=\id_{\cat{Std}}$, $G\circ F\circ H$ is equivalent to $\id_{\cat{Bdl}_{\mathrm{sur}}}$, and $F\circ H\circ G=\id_{\cat{Part}}$. In particular, these three categories are equivalent ($\cat{Std}$ and $\cat{Part}$ being in fact isomorphic). We will, therefore, not make any meaningful distinction between these concepts.

Bundles are generally easier to describe in the topological setting: A continuous or topological bundle is a continuous map $\pi\colon X^{(1)}\to X^{(0)}$ between topological spaces. In this setting, we also consider only bundle morphisms $f=(f^{(1)},f^{(0)})$ such that $f^{(0)}$ and $f^{(1)}$ are continuous. Equivalently, continuous bundles and their morphisms form the category of arrows of $\cat{Top}$, the category of topological spaces and continuous maps.

Given bundles (fibrations) $\pi_i\colon X_i\to X^{(0)}$ ($i=1,2,$) over the same base space $X^{(0)}$, the fibred product of $\pi_1$ and $\pi_2$ is

1.2. Graphs

Graphs will be used in the description of semigroupoids, and provide a geometric picture which will be useful throughout this paper. The graphs we consider are sometimes called directed multigraphs, since all edges come with a direction and we allow multiple edges between points.A graph is a tuple $G=(G^{(0)},G^{(1)},\so,\ra)$, where $G^{(0)}$ and $G^{(1)}$ are classes of vertices and arrows, respectively, and $\so,\ra\colon G^{(1)}\to G^{(0)}$ are functions, called the source and range maps.

Alternative terminology is sometimes employed. Elements of $G^{(0)}$ are also called objects or units; elements of $G^{(1)}$ are called edges; The source map is also called the domain map, and the range map the target or codomain map. We may alternate between these terminologies depending on the context. If necessary, we will use subscripts to specify the graph $G$, as in writing $\so_G$ and $\ra_G$.

We usually write simply $G$ in place of $G^{(1)}$, so that an inclusion of the form $g\in G$ means that $g$ is an arrow of $G$.

Note that the source and range maps give fibred structures on $G^{(1)}$ over $G^{(0)}$. Moreover, we will generally assume that $G=\so(G)\cup\ra(G)$, in the same manner that surjective bundles are the ones of interest.

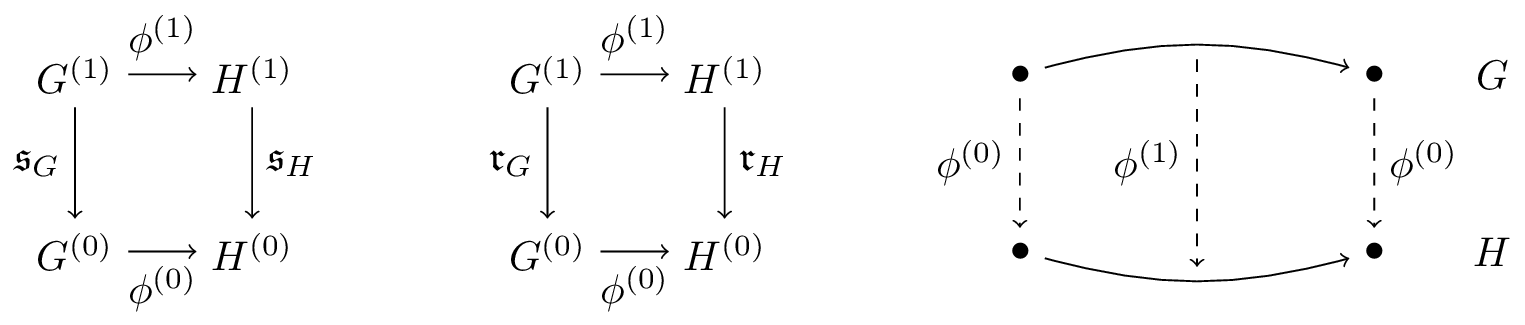

A graph morphism $\phi\colon G\to H$ between graphs $G$ and $H$ is a pair $\phi=(\phi^{(0)},\phi^{(1)})$ of maps $\phi^{(0)}\colon G^{(0)}\to H^{(0)}$ and $\phi^{(1)}\colon G^{(1)}\to H^{(1)}$ such that $\so_H\circ\phi^{(1)}=\phi^{(0)}\circ\so_G$ and $\ra_H\circ\phi^{(1)}=\phi^{(0)}\circ\ra_G$. In other words, it is a simultaneous fibred morphism from $G$ to $H$ over their respective source and range maps. A graph isomorphism is a graph morphism $\phi$ such that both $\phi^{(0)}$ and $\phi^{(1)}$ are bijective, and in this case $\phi^{-1}=((\phi^{(0)})^{-1},(\phi^{(1)})^{-1})$ is also a graph morphism.

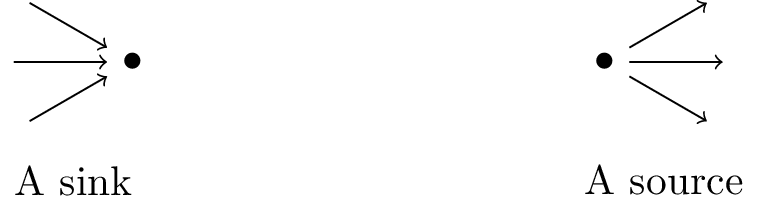

A sink in a graph is a vertex $v\in G^{(0)}$ such that $\so^{-1}(v)=\varnothing$. A source in a graph is a vertex $v\in G^{(0)}$ such that $\ra^{-1}(v)=\varnothing$.

We also regard $G^{(0)}$ as a trivial graph with vertex set $G^{(0)}$, and the source and range maps the identity function: $\so,\ra=\id_{G^{(0)}}$.

If $G$ and $H$ are graphs over the same vertex set $G^{(0)}=H^{(0)}$, we make the fibred product $G\left.\right._{\so}\!\!\ast_{\ra} H$ into a graph over that same vertex set, with source and range maps $\ra(g,h)=\ra(g)$ and $\so(g,h)=\so(h)$. The construction of graphs of paths obey the “rules of exponentiation”, where the fibred product $\left.\right._{\so}\!\!\ast_{\ra}$ takes the role of the product: given $k,p\in\mathbb{N}_{\geq 0}$, we have natural isomorphisms